I have finally been sorting through the saved flood-damaged files and photos, not without much regret and a few tears, throwing out many, reviving some and surmising what must have been deemed beyond hope and tossed by my helpers in the flood aftermath.

My daughter had dried these curling and stuck-together remnants; I just have not been able to face them.

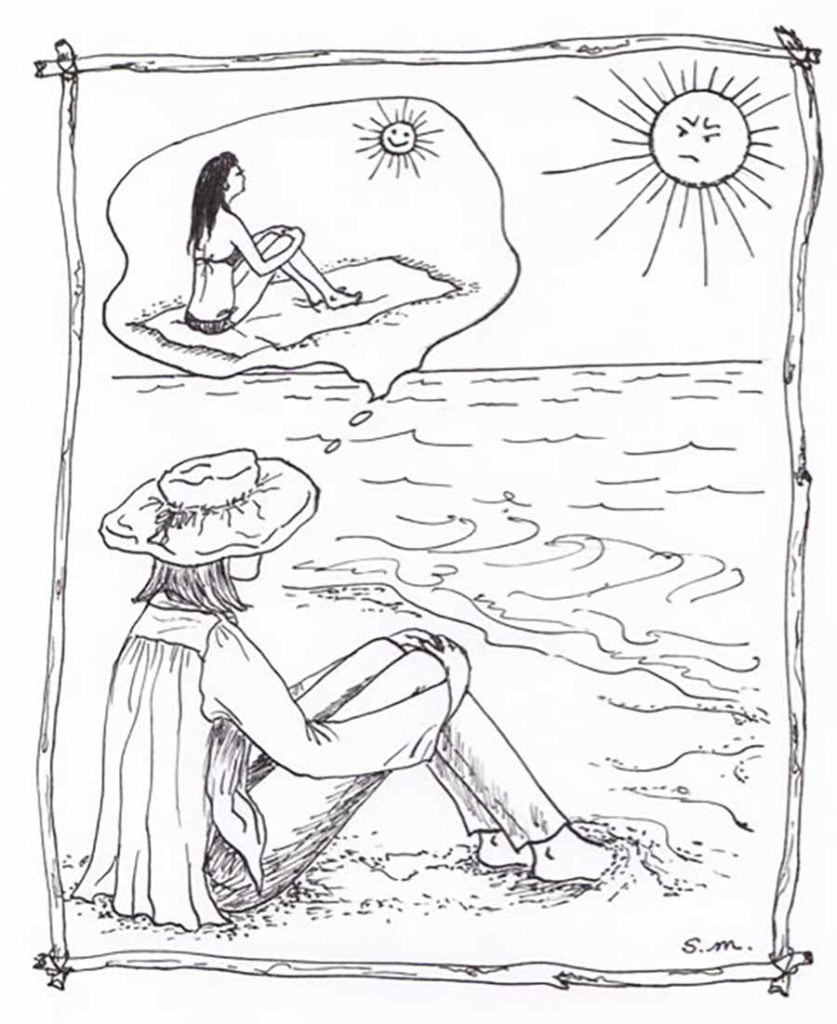

I came across this drawing, intended for what I can’t recall, but it did set me reminiscing on just how primitive were the bathing facilities … and the leaky tank water supply… with which I grew up.

No shower, a once-a-week bath in inches of water, daily face and hands washing in a basin on a chair, which was then set on the floor for feet washing while one sat on the chair. And we did not get a bath or a basinful each, but shared it: Mum first, then down through the sisters, with Dad last.

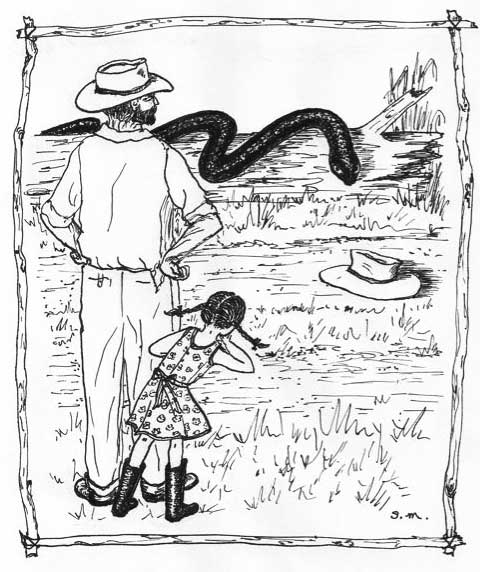

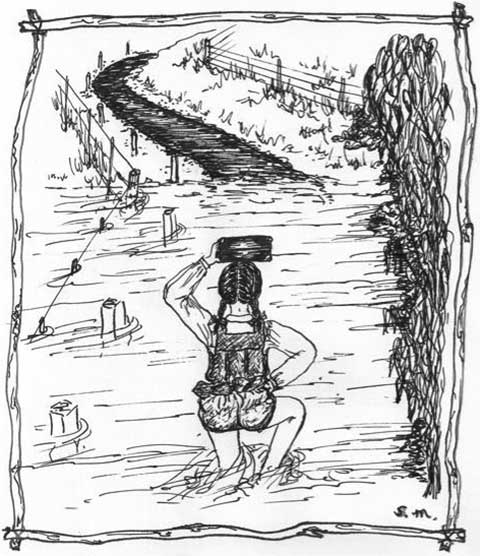

The once-a-week hair washing was done over the cement laundry tubs, with a jug of warm water for rinsing. For years I was too short to do this comfortably, as the drawing shows!

The wood-fired copper heated the water for Mum’s washing, with a water-furred stick for stirring the clothes and for lifting them out to the adjacent tubs for rinsing.

Mum did have a small cloth bag of Bluo for special whites and a slab of rough sandsoap for Dad’s really dirty work clothes.

But overall one soap did all this, plus being grated into the wire mesh soap holder for dishwashing: a plain yellow bar of Sunlight, the sort that would now be considered only fit for the laundry.

The dishwashing was done in another dish, on the kitchen table, with a metal tray beside it for the brief draining of dishes before our tea towels seized them. There was no hot water on tap in kitchen, bathroom or laundry. The kettle on the fuel stove heated the washing-up water, while a ferocious and highly unpredictable chip heater loomed at the end of the claw-footed bath for the daring to light.

How did we survive without the hundreds of options in personal soaps, bodywashes, shampoos, conditioners, water softeners, pre-washes, stain removers, laundry powders or liquids?

How did my mother?!!

I can still recall the wonder of my first shower, elsewhere, as a late teenager.

So my years of outdoor bush showers and washing at the kitchen sink at the Mountain were not hard; they were luxuries!

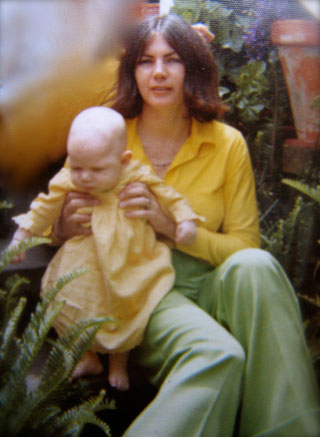

I am feeling rather nostalgic for the days when my adult children were babies. This has been brought on by the fact that my first-born is turning 38 this month!

I am feeling rather nostalgic for the days when my adult children were babies. This has been brought on by the fact that my first-born is turning 38 this month!