The latest unthinkable area to be targeted by the coal mining frenzy is the world-renowned wine and food area of Margaret River in south-west Western Australia.

A town, a river and a region, it is one of that state’s main tourist destinations, offering a Mediterranean climate and a combination of surf coast and scenic hinterland as settings for rich and varied cultural and gastronomic experiences.

The people who moved there and gradually created this special — and sustainable — economic Eden know what they have to offer. They also know what they have to lose if the coal industry gets a toehold here.

Bye-bye Leederville aquifer, bye-bye rural peace and quiet, bye-bye Margaret River as a holiday refuge for the city-stressed.

This is the mine site on Osmington Rd, near Rosa Brook, 15km from the actual town of Margaret River, and a much-visited and picturesque part of the Margaret River region, with wineries, dairies, berry and olive farms, equestrian centres and charming rural B&Bs, like the owner-built Rosa Brook Stone where I stayed.

LD Operations is currently applying to mine coal underground here; other exploration leases await. As you can see from the swampy centre, it’s clearly a wet area, despite, as locals say, a dry winter.

It is inconceivable that they will be able to mine without damaging the aquifer, although I am sure they will find experts to assure us that this would be ‘unlikely’.

The visible neighbouring farmhouses are modern, new-ish; they weren’t expecting this. Nor were these inhabitants of the adjoining lifestyle block.

Locals like TV chef Ian Parmenter (left) and Brent Watson have formed a strong NoCOAL!itionmargaretriver group to fight this entirely inappropriate mine.

Locals like TV chef Ian Parmenter (left) and Brent Watson have formed a strong NoCOAL!itionmargaretriver group to fight this entirely inappropriate mine.

Ian Parmenter and his wife Ann moved here 20 years ago, building a haven — home and garden and orchard and vineyard — over that time. Brent Watson and his family run the highly successful Horses and Horsemen equestrian resort and training centre just down the road.

They have the support of the local Council, winemakers and tourism associations and notables such as James Halliday. Local member Troy Buswell says he’s agin it, but Premier Colin Barnett has finally stated that he is not about to step in and deny LDO their ‘due process’

And we all know what that portends.

Because I was visiting Collie, only two hours away, Ian asked me to speak at a public meeting the day before I headed home. About 70 people turned up at the Rosa Brook Hall to hear about what I’ve seen in coal areas in other states and were audibly shocked at the Rivers of Shame DVD shown afterwards. As a reward, I was treated to a Parmenter feast of a dinner — vegetarian, in my honour!

I know these good people had very full lives and livelihoods before this mine threat exploded and I know how much time they are now spending on trying to save them — and the future and water resources of the whole region. This is a huge part of the unfairness I see all around the country. I hope they can last the distance — and win — as all reason and justice say they ought.

If Mr Barnett is not thinking of the southwest’s water and longterm land use, he might like to think about this, which I’d read before this whole mining madness became public. It’s was in The Weekend Australian Financial Review May 22-23, 2010, ‘How space and place dictate your happiness’ by Deirdre Macken. She reported that Glenn Albrecht, Professor of Sustainability at Murdoch University, had studied the Upper Hunter’s existentially distressed coal mining area populations, where ‘everything they valued was being taken away, … shovel by shovel’.

He became interested in finding places that work best for people, ‘health-enhancing environments’, and he and urban planner Roberta Ryan of Urbis independently agreed that ‘the place in Australia that best captures the qualities that please the psyche is the Margaret River.’

Says Ryan, ‘It’s the most extraordinary place… and it just feels like the most fantastic place to be. It helps that it has an incredible level of investment by locals and so the locals feel as if it’s owned by them.’

Which is why they won’t be allowing Mr Barnett to allow the mining company, under his rubber stamp legislation, to take it away from them — and the rest of us.

About 80 km south-west of Bowen in Queensland is the historic mining town of Collinsville. They’re proud of their strong coalmining and union past here — as the saga of underground strikes and fatal accidents and protest convoys to Brisbane attests. I know this from the coal museum

About 80 km south-west of Bowen in Queensland is the historic mining town of Collinsville. They’re proud of their strong coalmining and union past here — as the saga of underground strikes and fatal accidents and protest convoys to Brisbane attests. I know this from the coal museum  Just west of Collinsville is the tiny village of Scottsville. Here I am to stay with Carol and Vince Cosentino at Wurra Yumba — Kangaroo House — who have a very pleasant accommodation building in their garden, which really belongs to a menagerie of rescued wildlife on the mend.

Just west of Collinsville is the tiny village of Scottsville. Here I am to stay with Carol and Vince Cosentino at Wurra Yumba — Kangaroo House — who have a very pleasant accommodation building in their garden, which really belongs to a menagerie of rescued wildlife on the mend. But it is actually Carol’s village of Scottsville that is closest to the Collinsville opencut mine.

But it is actually Carol’s village of Scottsville that is closest to the Collinsville opencut mine. At night, a drive along a hilltop road revealed how huge this mine is, or so I thought; but satellite maps show me it is far bigger.

At night, a drive along a hilltop road revealed how huge this mine is, or so I thought; but satellite maps show me it is far bigger. And the newer Sonoma mine is far too close as well. There has been a coal-fired power station here since 1976, and with what I know from the Hunter, the combination does not augur well for the health of Scottsville and Collinsville residents.

And the newer Sonoma mine is far too close as well. There has been a coal-fired power station here since 1976, and with what I know from the Hunter, the combination does not augur well for the health of Scottsville and Collinsville residents. Lately I went to look at the coal mining explosion in Queensland, to see for myself if it was as frighteningly out of control as that in NSW. It is.

Lately I went to look at the coal mining explosion in Queensland, to see for myself if it was as frighteningly out of control as that in NSW. It is. The coal comes by rail in trains up to 2 km long, uncovered, passing through Central Queenland for up to 300 km to the two major coal loading export terminals, Dalrymple Bay and Hay Point. These extend far out into the bay, 3.85 km and 1.8 km respectively.

The coal comes by rail in trains up to 2 km long, uncovered, passing through Central Queenland for up to 300 km to the two major coal loading export terminals, Dalrymple Bay and Hay Point. These extend far out into the bay, 3.85 km and 1.8 km respectively.

At the viewing parks, large signs boast of the output and the environmental care being taken, and invite me to follow the Mining Trail inland to the mining towns that feed this port. I did, but I doubt my reaction was the intended one.

At the viewing parks, large signs boast of the output and the environmental care being taken, and invite me to follow the Mining Trail inland to the mining towns that feed this port. I did, but I doubt my reaction was the intended one.

People had chosen to live here for the beauty, the fresh air, the peace and quiet – and not least the fishing – and sacrificed the convenience of shops. There were still a few fishermen by the creek the day I visited, but the peace and quiet no longer exists; I’d be concerned about the air — and I doubt I’d be beach fishing.

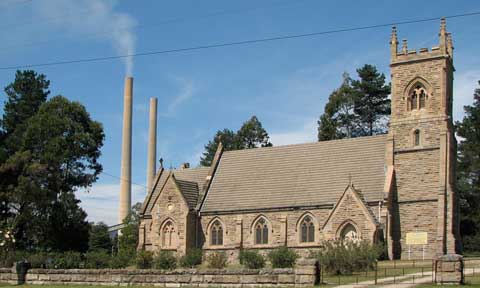

People had chosen to live here for the beauty, the fresh air, the peace and quiet – and not least the fishing – and sacrificed the convenience of shops. There were still a few fishermen by the creek the day I visited, but the peace and quiet no longer exists; I’d be concerned about the air — and I doubt I’d be beach fishing. At Wallerawang power station the village of the same name is extremely close by, as the church shows. I wonder if the residents are aware of the toxic contents of those plumes of smoke? In the Hunter, Ravensworth, once probably the closest village to those power stations, is now obliterated, the abandoned school the only testament that once it thrived.

At Wallerawang power station the village of the same name is extremely close by, as the church shows. I wonder if the residents are aware of the toxic contents of those plumes of smoke? In the Hunter, Ravensworth, once probably the closest village to those power stations, is now obliterated, the abandoned school the only testament that once it thrived. Why doesn’t the government take the cumulative effects of these approvals into account? It must seem to Blackmans Flat residents that it’s because people don’t count.

Why doesn’t the government take the cumulative effects of these approvals into account? It must seem to Blackmans Flat residents that it’s because people don’t count.

As the valley fills with dust and noise, the cliffs split and fall away and the filtering hanging swamps drain dry through the cracks from undermining, we must remind ourselves that all these operations are under ‘strict environmental guidelines’.

As the valley fills with dust and noise, the cliffs split and fall away and the filtering hanging swamps drain dry through the cracks from undermining, we must remind ourselves that all these operations are under ‘strict environmental guidelines’. I wonder if Lithgow Council, who support the third power station, know what they are allowing to happen to their scenic region and its inhabitants. While underground mines currently dominate here, unlike the Hunter’s open-cut moonscape, the pollution and the destructive impacts are increasing and so are the mines.

I wonder if Lithgow Council, who support the third power station, know what they are allowing to happen to their scenic region and its inhabitants. While underground mines currently dominate here, unlike the Hunter’s open-cut moonscape, the pollution and the destructive impacts are increasing and so are the mines. Trish Duddy and Tommy and George Clift (front L to R, all hatted) have been at the blockade camp every single one of those 615 days, joined by other locals on a rolling roster for cups of tea, information swapping, resolve steeling — and symbolic trailblazing.

Trish Duddy and Tommy and George Clift (front L to R, all hatted) have been at the blockade camp every single one of those 615 days, joined by other locals on a rolling roster for cups of tea, information swapping, resolve steeling — and symbolic trailblazing. I had driven in to the Blockade that morning, looking south across the Plains to the polluted and dust-laden skies of the Hunter Valley, where the government has allowed every coal company to win every battle. Down there it is the wineries and thoroughbred horse studs now protesting that their industries cannot cope with any more coal mines.

I had driven in to the Blockade that morning, looking south across the Plains to the polluted and dust-laden skies of the Hunter Valley, where the government has allowed every coal company to win every battle. Down there it is the wineries and thoroughbred horse studs now protesting that their industries cannot cope with any more coal mines. The difference when I looked north, away from the coal-trashed Hunter, is obvious – clear blue skies as country skies should be, not murky brown. I admired the vast patchwork of ploughed land and crops, with the rusty red of sorghum seed-heads, the green of new crops, the cream of harvested stubble and the rich dark soil itself.

The difference when I looked north, away from the coal-trashed Hunter, is obvious – clear blue skies as country skies should be, not murky brown. I admired the vast patchwork of ploughed land and crops, with the rusty red of sorghum seed-heads, the green of new crops, the cream of harvested stubble and the rich dark soil itself. Later that day, heading towards the hills and home, I pass incredibly flat golden vistas of sunflower heads and their vibrant green plants and I am struck by its ‘livingness’ as I think of the appalling contrast I will meet back as I drive back into the Hunter.

Later that day, heading towards the hills and home, I pass incredibly flat golden vistas of sunflower heads and their vibrant green plants and I am struck by its ‘livingness’ as I think of the appalling contrast I will meet back as I drive back into the Hunter. Vistas of dirt and coal, an industrial hell, a dead landscape, seen through the veil made by one of the highest concentrations of fine dust particulates in Australia. I hope the Caroona farmers manage to stop this happening to their Plains — and after speaking to many of them I believe they will!

Vistas of dirt and coal, an industrial hell, a dead landscape, seen through the veil made by one of the highest concentrations of fine dust particulates in Australia. I hope the Caroona farmers manage to stop this happening to their Plains — and after speaking to many of them I believe they will! In the Goulburn River National Park north of Mudgee, from The Drip picnic area, I recently took the easy 1.5km walk beside the river to the fabulous and deservedly famous Drip gorge formation.

In the Goulburn River National Park north of Mudgee, from The Drip picnic area, I recently took the easy 1.5km walk beside the river to the fabulous and deservedly famous Drip gorge formation. The sandy path led me under massive balancing acts and grotesque weatherings of ancient rocks. The river was gentle now but the effects of its different moods were evident on the cliffside banks. From the footprints and scratchings in the sand of the depressions and overhangs, it was clear that many animals use the shelters and overhangs.

The sandy path led me under massive balancing acts and grotesque weatherings of ancient rocks. The river was gentle now but the effects of its different moods were evident on the cliffside banks. From the footprints and scratchings in the sand of the depressions and overhangs, it was clear that many animals use the shelters and overhangs. And then I came to The Drip itself. Arching over my head, cantilevered layers of rock soared against the sky. Groundwater from the land above filtered through the strata and dripped steadily into the pools below. The scale of this cliff was majestic, yet the gravity-defying structure felt fragile. I am sure nature knows what it’s doing — only an earthquake will bring this down.

And then I came to The Drip itself. Arching over my head, cantilevered layers of rock soared against the sky. Groundwater from the land above filtered through the strata and dripped steadily into the pools below. The scale of this cliff was majestic, yet the gravity-defying structure felt fragile. I am sure nature knows what it’s doing — only an earthquake will bring this down. North of Mudgee, NSW, I recently visited such a home. It now has a new open-cut coal mine as a neighbour that can’t be ignored. That huge wall of overburden (the dirt and rock they dig up to get at the coal) is just 400 metres from their house, rising beside the small creek in the treeline. You can just see the top of one of the giant trucks operating there.

North of Mudgee, NSW, I recently visited such a home. It now has a new open-cut coal mine as a neighbour that can’t be ignored. That huge wall of overburden (the dirt and rock they dig up to get at the coal) is just 400 metres from their house, rising beside the small creek in the treeline. You can just see the top of one of the giant trucks operating there. I travel south to see another mine in the region, down a pot-holed dirt road with mine vehicles hurtling along it at speeds that make me pull over to get out of the way.

I travel south to see another mine in the region, down a pot-holed dirt road with mine vehicles hurtling along it at speeds that make me pull over to get out of the way. I leave the mines behind and head down a dirt road in what seems a green and still rural valley to find a spot to have my picnic lunch. It is quiet enough, but then over the green hills I see dust rising; I have not gone far enough to escape the effect of the open-cut, although the mine would probably have classed this valley as beyond its ‘area of affectation’.

I leave the mines behind and head down a dirt road in what seems a green and still rural valley to find a spot to have my picnic lunch. It is quiet enough, but then over the green hills I see dust rising; I have not gone far enough to escape the effect of the open-cut, although the mine would probably have classed this valley as beyond its ‘area of affectation’.