As central Queensland floods, I am hearing much in the media about the economic damage to the coal mines there, but not what those mines are contaminating as the floods surge through them. Or as the exposed coal stockpiles at every mine, rail loader and port loader wash into the floods.

When the town of Theodore was evacuated, I immediately thought of the flatness of the country and the road to Theodore, which runs for kilometres beside the Moura mine’s heavy metal-laden overburden dumps, now washing into the rushing flood, and of their contaminated mine water, usually stored in earth-walled tailings dams.

And if you ever thought road and rail were solid things, just look at how they have been pushed aside by water — lifted like frosting on a cake, as shown by this photo of the Banana to Theodore route, passed on by Avriel Tyson from near Rolleston.

What will such power have done in all the mines up there?

In previous floods, such walls have broken or been overflowed, and mines fined (tuppence!), as at the Ensham and Rolleston mines in the Emerald region, for releasing these toxic waste waters into the river system — and hence to the Great Barrier Reef. This photo, of the Rolleston mine flooding in that previous event, was taken by Avriel Tyson.

The Tysons have been isolated on their homestead island of slightly higher ground (which I had thought was flat when I was there) by the current unprecedentedly high flooding since late December, creeks breaking their banks that never have before, their road washed away — one of their heifers turning up 20 kilometres away! — and they are told that the next-door mine has had two metres of water over its railway line.

As the waters dropped, Avriel took photos of flooded Sandy Creek near their boundary, with the Xstrata mine behind.

Tysons have been here for over 100 years but Avriel says that this is a first; that the normal flood direction is baulked by the mine’s ‘ring tank levees and overburden piles’.

She wonders what the mine is doing with its water, and, looking at the debris on the fence and grid at their boundary with the mine, I too wonder what invisibles the mine has deposited.

Farmers expect to work with flood plain systems, mines can’t.

There are about 40 mines in the Bowen Basin, many of which interfere with the natural spread and flow system of floodwaters, their massive earthworks blocking and channelling so the plain no longer functions as nature designed.

In the Surat Basin, increasingly sieved with a network of gas wells and test bore holes — Taroom, Chinchilla, Dalby — what will the aftermath damage be from all the submerged and tumbled drilling sites and pipelines? The photo above, passed on by Avriel, is on the Taroom/Roma road.

Mine management ‘plans’ for hazardous materials and wastes may tick the government boxes for approval but they only work on paper, not on the flood plains. Thirty more mines are planned for the Bowen Basin in the next five years, and half of the existing 40 are expanding.

Poisoned river systems, poisoned silt deposited on farmland? We need to hear from the mining industry how they are dealing with this aspect of multliple flooded mines, not just how it will hurt their profit margins.

But the worst part was when the New Hope representative stepped forward to lay a wreath. The sudden intensity of the silence and the sharply focused resentment should have felled him on the spot if he had any sensitivity about what his company had done, was doing to these people. This was not any Anzac Day ceremony; New Hope could have laid a wreath somewhere else if they wanted to pay homage. Like any enemy soldier, he would have acted under orders, but it would surely have occurred to them that as the invaders, the perpetrators, they should not be present as people here grieved, not just for the fallen soldiers, but for the fall of Acland.

But the worst part was when the New Hope representative stepped forward to lay a wreath. The sudden intensity of the silence and the sharply focused resentment should have felled him on the spot if he had any sensitivity about what his company had done, was doing to these people. This was not any Anzac Day ceremony; New Hope could have laid a wreath somewhere else if they wanted to pay homage. Like any enemy soldier, he would have acted under orders, but it would surely have occurred to them that as the invaders, the perpetrators, they should not be present as people here grieved, not just for the fallen soldiers, but for the fall of Acland.

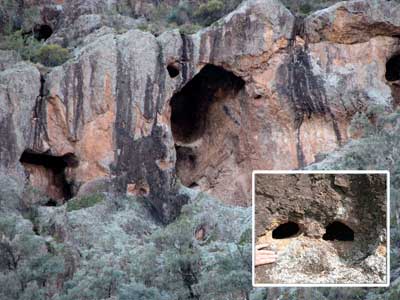

If you became homeless because your house was being demolished, obviously you’d have to find a new home to live in. It’s no different for other animals; we all need shelter, a home, habitat.

If you became homeless because your house was being demolished, obviously you’d have to find a new home to live in. It’s no different for other animals; we all need shelter, a home, habitat.

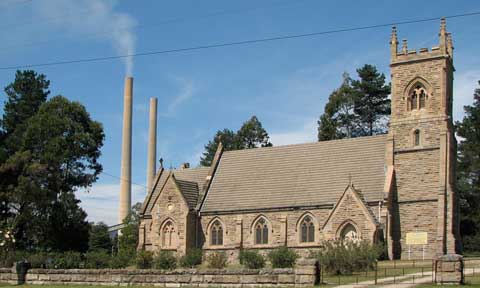

At Wallerawang power station the village of the same name is extremely close by, as the church shows. I wonder if the residents are aware of the toxic contents of those plumes of smoke? In the Hunter, Ravensworth, once probably the closest village to those power stations, is now obliterated, the abandoned school the only testament that once it thrived.

At Wallerawang power station the village of the same name is extremely close by, as the church shows. I wonder if the residents are aware of the toxic contents of those plumes of smoke? In the Hunter, Ravensworth, once probably the closest village to those power stations, is now obliterated, the abandoned school the only testament that once it thrived. Why doesn’t the government take the cumulative effects of these approvals into account? It must seem to Blackmans Flat residents that it’s because people don’t count.

Why doesn’t the government take the cumulative effects of these approvals into account? It must seem to Blackmans Flat residents that it’s because people don’t count.

As the valley fills with dust and noise, the cliffs split and fall away and the filtering hanging swamps drain dry through the cracks from undermining, we must remind ourselves that all these operations are under ‘strict environmental guidelines’.

As the valley fills with dust and noise, the cliffs split and fall away and the filtering hanging swamps drain dry through the cracks from undermining, we must remind ourselves that all these operations are under ‘strict environmental guidelines’. I wonder if Lithgow Council, who support the third power station, know what they are allowing to happen to their scenic region and its inhabitants. While underground mines currently dominate here, unlike the Hunter’s open-cut moonscape, the pollution and the destructive impacts are increasing and so are the mines.

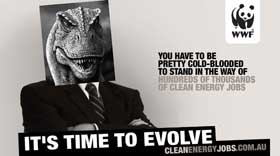

I wonder if Lithgow Council, who support the third power station, know what they are allowing to happen to their scenic region and its inhabitants. While underground mines currently dominate here, unlike the Hunter’s open-cut moonscape, the pollution and the destructive impacts are increasing and so are the mines. In the months before the international climate conference in Copenhagen the dinosaurs of the coal industry are spending up big on lobbying to keep things the way they like them and helping the usual crew of Parliamentary dinosaurs to block the creation of hundreds of thousands of badly needed new clean energy jobs.

In the months before the international climate conference in Copenhagen the dinosaurs of the coal industry are spending up big on lobbying to keep things the way they like them and helping the usual crew of Parliamentary dinosaurs to block the creation of hundreds of thousands of badly needed new clean energy jobs. They tempt you to walk into the wild side, but with safety, and to experience the greatly varied vegetation of the surrounding bush.

They tempt you to walk into the wild side, but with safety, and to experience the greatly varied vegetation of the surrounding bush. Robert has chosen the paths to take you through hillside forests and gully jungles, past luminous blue gums and thriving cabbage tree palms, the oldest, wartiest paperbark tree I have ever seen…

Robert has chosen the paths to take you through hillside forests and gully jungles, past luminous blue gums and thriving cabbage tree palms, the oldest, wartiest paperbark tree I have ever seen… …and battle-scarred eucalypts so tall I can hardly see their tops.

…and battle-scarred eucalypts so tall I can hardly see their tops.

Kangaroos laze in security by Grecian columns; semi-naked ladies swoon by equally ‘palely loitering’ Blue Gums; a multitude of birds other than waterbirds are attracted to the water – such as a flock of White-headed Pigeons.

Kangaroos laze in security by Grecian columns; semi-naked ladies swoon by equally ‘palely loitering’ Blue Gums; a multitude of birds other than waterbirds are attracted to the water – such as a flock of White-headed Pigeons.

I was able to sneak a few days after recent book talk commitments out west to meet two cousins who were going camping in the Warrumbungle National Park near Coonabarabran, New South Wales,

I was able to sneak a few days after recent book talk commitments out west to meet two cousins who were going camping in the Warrumbungle National Park near Coonabarabran, New South Wales,