Once the fog had lifted from the Latrobe Valley, the old Hazelwood Power Station near Morwell showed the true colour of its emissions — brown. Of course the real toxic output of such an outmoded technology — CO2 — is colourless, and all the more insidious for being invisible and thus unacted upon. Hazelwood produces 16 million tonnes of greenhouse gases each year — 15 per cent of Victoria’s total emissions.

It is also Australia’s largest single source of dioxin pollution.

Due to close in 2005, its private owners asked, and were given permission, to keep pumping them out until 2031.

The brown sky trail edged around the valley for kilometres, still clearly visible beyond Traralgon where it seemed to bank up against the hills in what was, for a Hunter person, a more familiar milky pollution mist. It was not fog.

In the newer power stations like Loy Yang A and B, the only visible output is the water vapour from the cooling towers. Looks harmless, doesn’t it? Almost clean! But while the CO2 emitted is less than at Hazelwood, it is still more than our planet can stand.

Brown coal contains about 65 per cent water, and is 33 per cent dirtier than black coal as a CO2 emitter.

There is much research afoot into various ways of drying it and reducing emissions — but mostly only to as much as black coal. Not good enough!

A few scraps of fog hung in the mine void, but no dust. For local impact, brown coal mining is amazingly clean and tidy compared to our Hunter open cut black coal mines. Loy Yang uses big excavators and conveyor belts, all run on its own electricity — very little diesel machinery.

I was sorry to hear that Yallourn mine had not replaced its excavators, but went to diesel power. I thought of the infrasound impacts of that, as well as the fossil fuel consumption.

Lately I went to look at the coal mining explosion in Queensland, to see for myself if it was as frighteningly out of control as that in NSW. It is.

Lately I went to look at the coal mining explosion in Queensland, to see for myself if it was as frighteningly out of control as that in NSW. It is. The coal comes by rail in trains up to 2 km long, uncovered, passing through Central Queenland for up to 300 km to the two major coal loading export terminals, Dalrymple Bay and Hay Point. These extend far out into the bay, 3.85 km and 1.8 km respectively.

The coal comes by rail in trains up to 2 km long, uncovered, passing through Central Queenland for up to 300 km to the two major coal loading export terminals, Dalrymple Bay and Hay Point. These extend far out into the bay, 3.85 km and 1.8 km respectively.

At the viewing parks, large signs boast of the output and the environmental care being taken, and invite me to follow the Mining Trail inland to the mining towns that feed this port. I did, but I doubt my reaction was the intended one.

At the viewing parks, large signs boast of the output and the environmental care being taken, and invite me to follow the Mining Trail inland to the mining towns that feed this port. I did, but I doubt my reaction was the intended one.

People had chosen to live here for the beauty, the fresh air, the peace and quiet – and not least the fishing – and sacrificed the convenience of shops. There were still a few fishermen by the creek the day I visited, but the peace and quiet no longer exists; I’d be concerned about the air — and I doubt I’d be beach fishing.

People had chosen to live here for the beauty, the fresh air, the peace and quiet – and not least the fishing – and sacrificed the convenience of shops. There were still a few fishermen by the creek the day I visited, but the peace and quiet no longer exists; I’d be concerned about the air — and I doubt I’d be beach fishing.

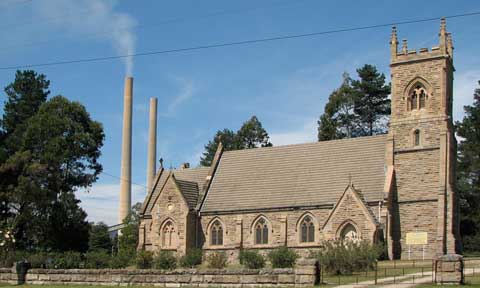

At Wallerawang power station the village of the same name is extremely close by, as the church shows. I wonder if the residents are aware of the toxic contents of those plumes of smoke? In the Hunter, Ravensworth, once probably the closest village to those power stations, is now obliterated, the abandoned school the only testament that once it thrived.

At Wallerawang power station the village of the same name is extremely close by, as the church shows. I wonder if the residents are aware of the toxic contents of those plumes of smoke? In the Hunter, Ravensworth, once probably the closest village to those power stations, is now obliterated, the abandoned school the only testament that once it thrived. Why doesn’t the government take the cumulative effects of these approvals into account? It must seem to Blackmans Flat residents that it’s because people don’t count.

Why doesn’t the government take the cumulative effects of these approvals into account? It must seem to Blackmans Flat residents that it’s because people don’t count.

As the valley fills with dust and noise, the cliffs split and fall away and the filtering hanging swamps drain dry through the cracks from undermining, we must remind ourselves that all these operations are under ‘strict environmental guidelines’.

As the valley fills with dust and noise, the cliffs split and fall away and the filtering hanging swamps drain dry through the cracks from undermining, we must remind ourselves that all these operations are under ‘strict environmental guidelines’. I wonder if Lithgow Council, who support the third power station, know what they are allowing to happen to their scenic region and its inhabitants. While underground mines currently dominate here, unlike the Hunter’s open-cut moonscape, the pollution and the destructive impacts are increasing and so are the mines.

I wonder if Lithgow Council, who support the third power station, know what they are allowing to happen to their scenic region and its inhabitants. While underground mines currently dominate here, unlike the Hunter’s open-cut moonscape, the pollution and the destructive impacts are increasing and so are the mines. In the Goulburn River National Park north of Mudgee, from The Drip picnic area, I recently took the easy 1.5km walk beside the river to the fabulous and deservedly famous Drip gorge formation.

In the Goulburn River National Park north of Mudgee, from The Drip picnic area, I recently took the easy 1.5km walk beside the river to the fabulous and deservedly famous Drip gorge formation. The sandy path led me under massive balancing acts and grotesque weatherings of ancient rocks. The river was gentle now but the effects of its different moods were evident on the cliffside banks. From the footprints and scratchings in the sand of the depressions and overhangs, it was clear that many animals use the shelters and overhangs.

The sandy path led me under massive balancing acts and grotesque weatherings of ancient rocks. The river was gentle now but the effects of its different moods were evident on the cliffside banks. From the footprints and scratchings in the sand of the depressions and overhangs, it was clear that many animals use the shelters and overhangs. And then I came to The Drip itself. Arching over my head, cantilevered layers of rock soared against the sky. Groundwater from the land above filtered through the strata and dripped steadily into the pools below. The scale of this cliff was majestic, yet the gravity-defying structure felt fragile. I am sure nature knows what it’s doing — only an earthquake will bring this down.

And then I came to The Drip itself. Arching over my head, cantilevered layers of rock soared against the sky. Groundwater from the land above filtered through the strata and dripped steadily into the pools below. The scale of this cliff was majestic, yet the gravity-defying structure felt fragile. I am sure nature knows what it’s doing — only an earthquake will bring this down. North of Mudgee, NSW, I recently visited such a home. It now has a new open-cut coal mine as a neighbour that can’t be ignored. That huge wall of overburden (the dirt and rock they dig up to get at the coal) is just 400 metres from their house, rising beside the small creek in the treeline. You can just see the top of one of the giant trucks operating there.

North of Mudgee, NSW, I recently visited such a home. It now has a new open-cut coal mine as a neighbour that can’t be ignored. That huge wall of overburden (the dirt and rock they dig up to get at the coal) is just 400 metres from their house, rising beside the small creek in the treeline. You can just see the top of one of the giant trucks operating there. I travel south to see another mine in the region, down a pot-holed dirt road with mine vehicles hurtling along it at speeds that make me pull over to get out of the way.

I travel south to see another mine in the region, down a pot-holed dirt road with mine vehicles hurtling along it at speeds that make me pull over to get out of the way. I leave the mines behind and head down a dirt road in what seems a green and still rural valley to find a spot to have my picnic lunch. It is quiet enough, but then over the green hills I see dust rising; I have not gone far enough to escape the effect of the open-cut, although the mine would probably have classed this valley as beyond its ‘area of affectation’.

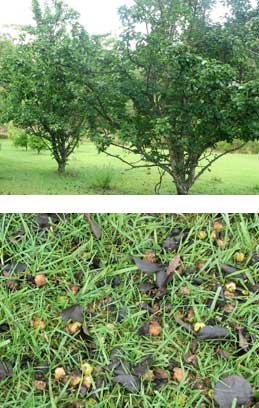

I leave the mines behind and head down a dirt road in what seems a green and still rural valley to find a spot to have my picnic lunch. It is quiet enough, but then over the green hills I see dust rising; I have not gone far enough to escape the effect of the open-cut, although the mine would probably have classed this valley as beyond its ‘area of affectation’.  Usually the parrots and I share the crop from my two large Nashi pear trees. I get hundreds of fruit from the lower branches and they take even more hundreds from the higher ones.

Usually the parrots and I share the crop from my two large Nashi pear trees. I get hundreds of fruit from the lower branches and they take even more hundreds from the higher ones. Crimson Rosellas like this one are a major culprit but so are the red and green King Parrots, who are more elusive — or guilty.

Crimson Rosellas like this one are a major culprit but so are the red and green King Parrots, who are more elusive — or guilty. Many farms, like the one below, have already been bought up for hard-to-resist prices; across other paddocks we could see dozens of test drill pipes under their white caps.

Many farms, like the one below, have already been bought up for hard-to-resist prices; across other paddocks we could see dozens of test drill pipes under their white caps. This region is watered by pristine rivers and creeks that rise in the nearby World Heritage sub-alpine Gloucester and Barrington Tops. And yet the mine wants to discharge its toxic waste water into these streams.

This region is watered by pristine rivers and creeks that rise in the nearby World Heritage sub-alpine Gloucester and Barrington Tops. And yet the mine wants to discharge its toxic waste water into these streams. These gullies run into Mammy Johnsons River (below), which flows to the Karuah River and thence to the tourist and marine environment mecca of Port Stephens.

These gullies run into Mammy Johnsons River (below), which flows to the Karuah River and thence to the tourist and marine environment mecca of Port Stephens.

And there was action. On the Saturday hundreds more concerned people joined us. We crouched down to form a human sign – ‘Cut carbon — now or never’ and a human ticking clock, which caused us to leap up and ‘explode’ over the oval at ‘midnight’. If you weren’t in the helicopter it wasn’t much of a photo opportunity, except for the rear end of the person in front!

And there was action. On the Saturday hundreds more concerned people joined us. We crouched down to form a human sign – ‘Cut carbon — now or never’ and a human ticking clock, which caused us to leap up and ‘explode’ over the oval at ‘midnight’. If you weren’t in the helicopter it wasn’t much of a photo opportunity, except for the rear end of the person in front!