In Nature nothing is wasted. Fallen and dead trees are habitat for fabulous fungi, and the damp conditions in these forests encourage them en masse.

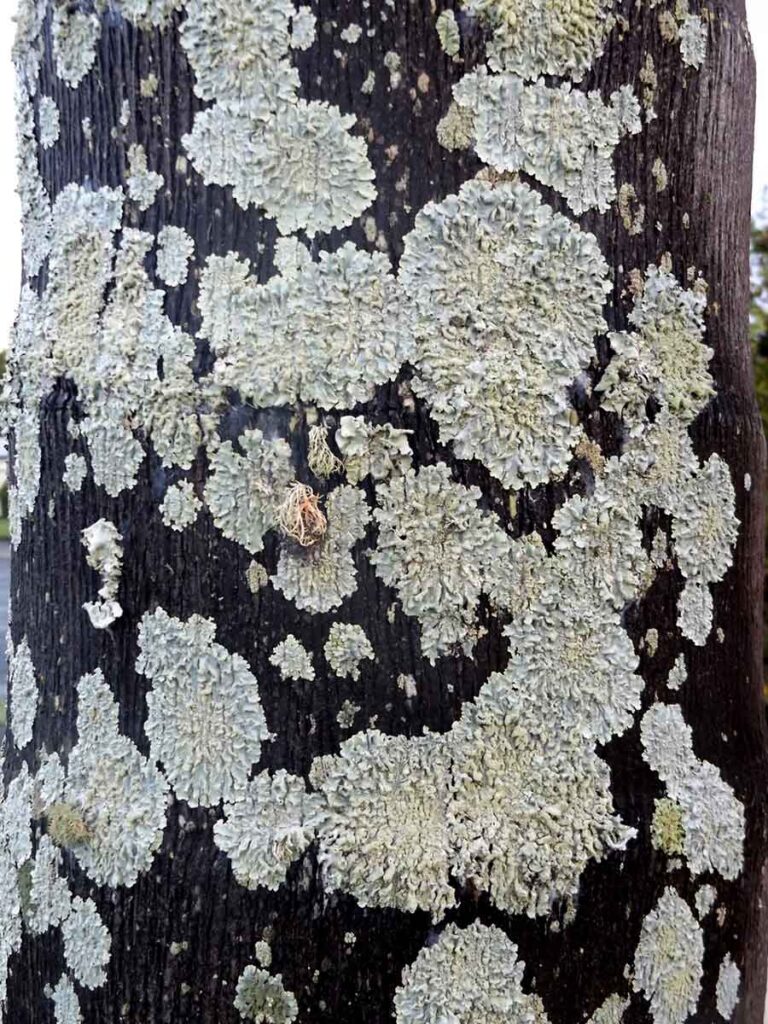

Some were solid and strange, unknown to me… unless someone had been sneaking about with a can of whitewash.

Others were like flowers, fringed and delicate fans.

Amidst the profusion of mossy green, orange and white stood out.

Less obvious, but more unusual, were these black ones, looking more like moths which, having briefly alighted on this log, were choosing to stay and transform into the most fanciful shapes.

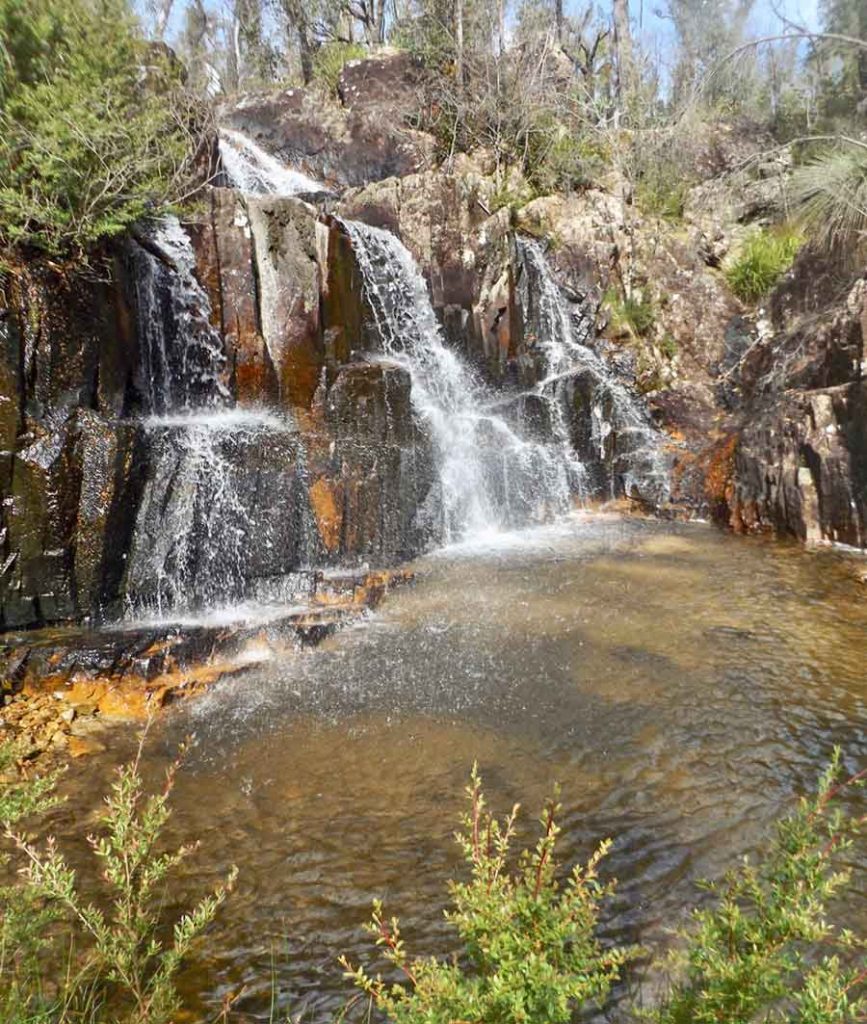

How beautiful is this cascade of snowy flakes?

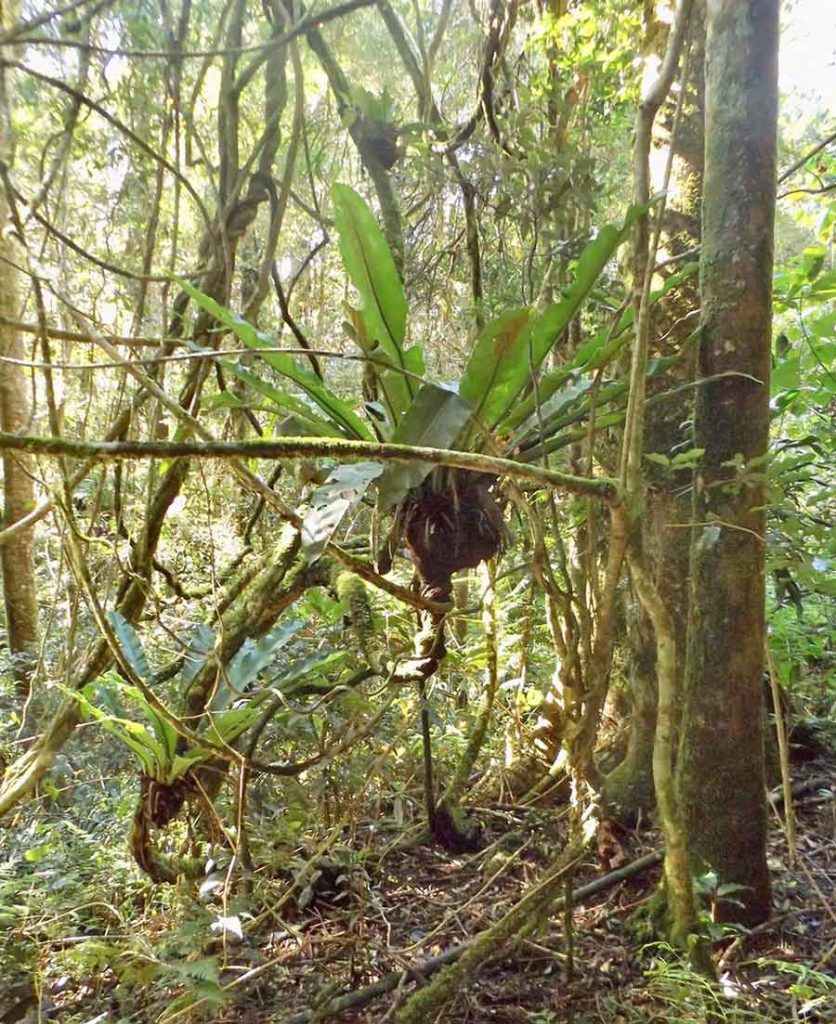

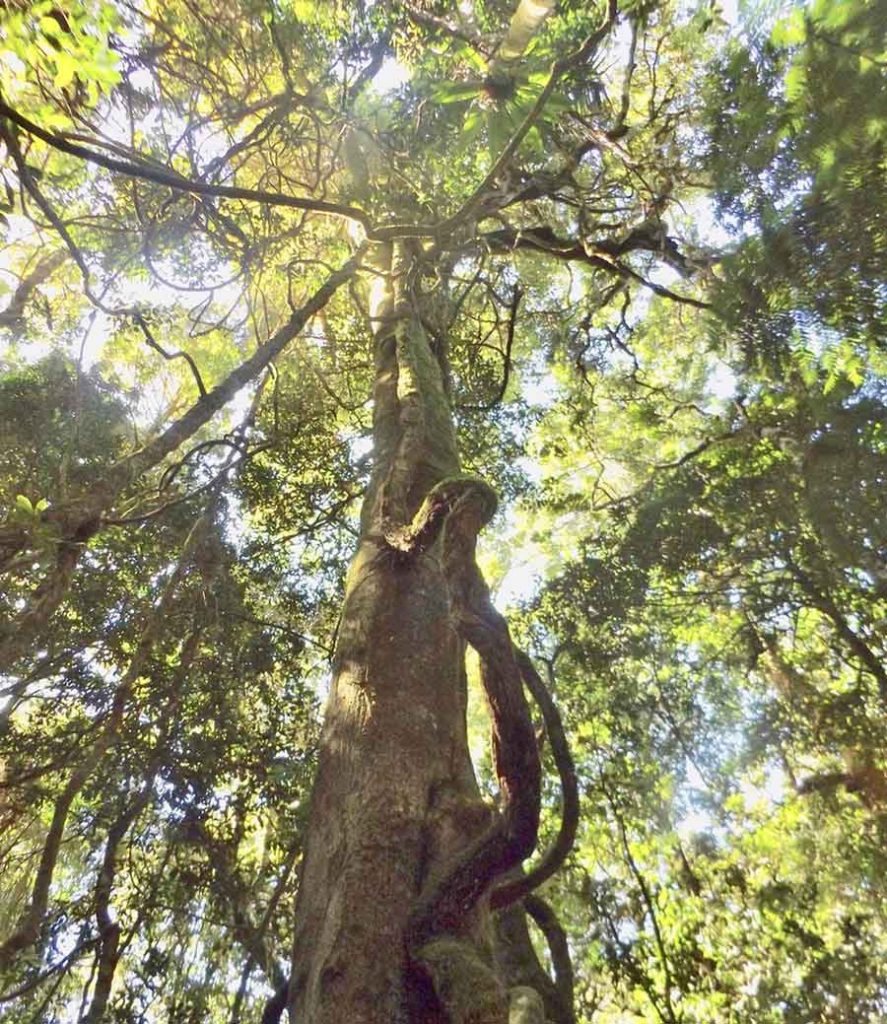

Whether weird or wonderful, abundance was the common theme in these tropical forests.

I do love moss and lichen, but fungi have my heart too.