Almost a day’s drive each way to spend a day ‘being there for Bylong’ at the IPC sessions in Mudgee on Wednesday 7th November re the Kepco Bylong Coal project. Many other folk made efforts too – and definitely not the ‘rentacrowd’ that some pro-mine speakers scoffed at. I don’t even like café lattes, but he told us all to go back to the city for them.

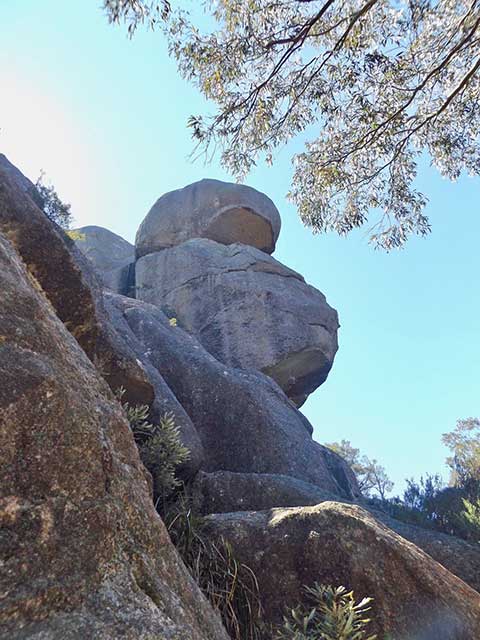

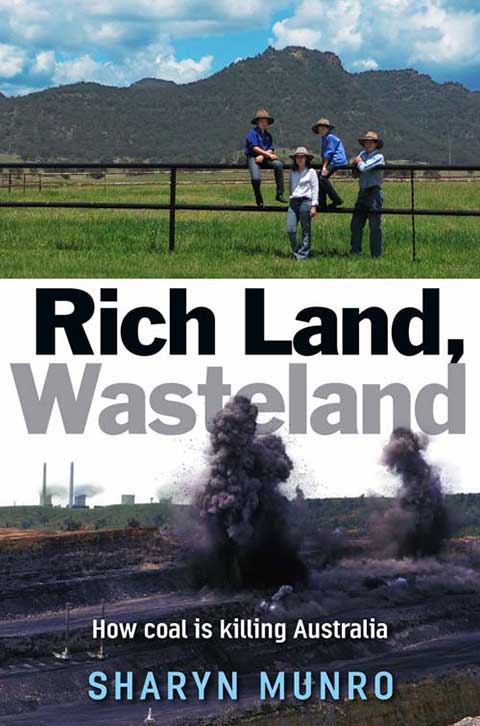

Whichever way you enter the stunning Bylong valley, from the Muswellbrook or the Rylstone ends, it is guarded by the most impressive cliffs. You feel as if you have been allowed into somewhere special, like Shangri-La. Which is why I chose it and the Andrews family at Tarwyn Park (now owned by Kepco) as the Rich Land for the cover of my book, Rich Land, Wasteland.

With subsidences predicted of up to 3.3 metres from the proposed mines’ longwalls, I fear for the cliffs that edge Bylong. The dozens of major cliff collapses south of Lithgow, from far less subsidence, is sickening.

Photo from the Battle for Bylong Facebook page

At the rally outside, prior to the day’s official speakers to the panel, locals and people from all over gathered to voice their support for Bylong. For me, it was like being at a funeral, where you are sad, but glad to see familiar faces; here too many were from past rallies or PAC hearings, from battles long-fought but lost, such as Wollar and Bulga.

Photo Tina Phillips

Inside, with 61 registered to speak, it was full until lunchtime at least. I noted the difference here, with no operating mine involved, as the room was not dominated by the high-vis shirts of mine employees.

Nevertheless there plenty of Mudgee business owners – motel, car sales, estate developers etc – crying doom if the Bylong mine did not go ahead; some speakers from Kandos pleaded for the jobs.

One farmer from Bylong commented tellingly on these calls, saying something like ‘so with three large mines you are not managing; will one small extra one save your businesses– and for how long?’

He and other Bylong farmers, and water experts, also set the record straight re the over-allocation of water there; the reality of water available is not what is on paper, and water sharing is needed, of when to pump and how much. And that is without a water-hungry mine.

It was often pointed out that the Ulan, Moolarben and Wilpinjong promises, predictions and modelling bore no relation to what actually happened/ is happening re water, noise, air pollution, traffic and social impacts. All are far, far more.

Is there no lesson to be learnt here?

Another mine so close to create cumulative impacts, yet this is not being taken into account.

The general inadequacy of Kepco’s research, modelling and plan, in water and economics, was made clear.

I was spitting chips at many aspects being treated with so little respect, but as always, it is the heartbreak for the people of Bylong that is the great injustice. As I only had 5 minutes, I concentrated on the social impacts.

And now we bide our time for Bylong.

Note that until 14th November you can still put in a written submission and be part of being there for Bylong through the Lock the Gate website.

This is what I said to the IPC panel:

In 2012 my book, Rich Land, Wasteland, on the impacts nationally of the rapid expansion of the coal and gas industries was released. I’d undertaken the two-year project because I’d watched modern mining being allowed to overwhelm and pollute the Hunter around Singleton and Muswellbrook.

The adverse air, water and health impacts were and are serious, with the most unfair impacts on rural lives. I saw the strain of the assessment years as began the fracturing, decimation and eventually obliteration of communities and the farming regions they’d served.

Once operations began, there was the immediate removal of quiet dark nights by a noisy industrial invader, and/or an insidious and heartstopping Low Frequency one, there was the sense of frustration at complaints being ignored, at monitoring manipulated to advantage, not truth, all the cards being held by the company, sales made in fear and desperation, confidentiality gags applied… and a pervasive sense of the Planning Dept being on the side of the company, and of the EPA being toothless.

‘Clearing out the country’ was my chapter on what happened to the Ulan, Cumbo and Wollar communities, and it’s mirrored in many places, like Bulga, Wybong, Camberwell…

I wanted my Rich Land cover image to convey family and farming traditions, good agricultural land, natural beauty, community, sustainability for generations. These were the resources to be valued above the mineral resources that seemed to have taken over the very meaning of the word ‘resources’ and whose short-term extraction, for private profit, was being allowed to destroy those environmental, agricultural and social riches.

I chose the Andrews family at Tarwyn Park in Bylong, for where else is the idea of sustainability so embodied in the land than in this living Natural Sequence Farming demonstration, even more important with climate change?

Yet here we are, facing the prospect of my iconic Rich Land losing many of those values, perhaps finally becoming more a museum surrounded by a Wasteland, as this project has been allowed to keep advancing despite acknowledged risks and inadequacies and deceptive practices. They have been coached to this point, when areas mapped as BSAL and CIC … and Tarwyn Park!… ought to have been off limits to exploration at the start.

Bylong Valley Protection Alliance fought hard to stop Bylong becoming a bygone place, its name signifying only a mine, like Warkworth. Nevertheless Kepco now own most of the properties, including the shop — the hub of the village — and a dozen or so families have left the Valley. People break, sell, and leave, yet the confidentiality clauses deny them the comfort of sharing experiences, or of helping those remaining.

And I’ve seen too many places where ‘stringent conditions’ as in your report are ignored or modifed, with too-few compliance officers to check often and at random. Too much ‘residual uncertainty’ remains here. How can you leave it to Kepco to use ‘adaptive management’ in so many areas, or to act on the better side in taking ‘all reasonable and feasible steps’ in others?‘Residual uncertainty’ ought to be like reasonable doubt in a court of law.

Elsewhere, despite all the conditions, cliffs have cracked and fallen away; water sources have drained and cannot be mended; make good promises are impractical and time-limited; the fight for recognition of LF impacts from Wilpinjong was hell for supposedly unimpactable residents; you do not mention blasts going wrong, sending orange nitrous oxide clouds over the valley, as happens too often in the Hunter or Maules Creek.

Our system has allowed Bylong’s social fabric to be broken; no matter how much you mandate Kepco’s community handouts they can’t replace things like the camaraderie of organising the Mouse Races to fund local needs.The oral history you propose is no substitute for the ongoing life of a community. A village is more than its buildings; it is people and their connections, it holds the history of the surrounding rural region, of gatherings, of families with generations, of pasts remembered… and futures hoped for.

Economic benefit for the wider region is no excuse for sacrificing Bylong; there are other ways for the state to gather revenue, and other ways to create jobs in non-harmful industries with a future.

It is NOT Ok for Planning to just note it inevitable that large mining projects have significant social impacts. Rather they should consider such a project inappropriate in that area and say no early. What was the Gateway for?

What is the point of a SIMP now? To survey the damage, to tart up the corpse? Or as at Wollar will this IPC say the damage is so great Kepco may as well finish off the job? Is the MidWest to be even further littered with tales of pain and heartache?

Whatever happened to a fair go?Our rural communities are an essential part of the fabric of Australia. Please don’t be responsible for Bylong becoming imore callous collateral damage from an industry that belongs to the past, before we knew how toxic it is to our world.

Communities are not just nuisances in the way of a coal project. Consider the moral rights, not only the mining rights, and say NO to this mine in an area that ought to have been off limits — and still should be.