Although I have lived in the area for several years now, I had never seen Lake Innes, never knew its story… or its real name, which is Burrawan.

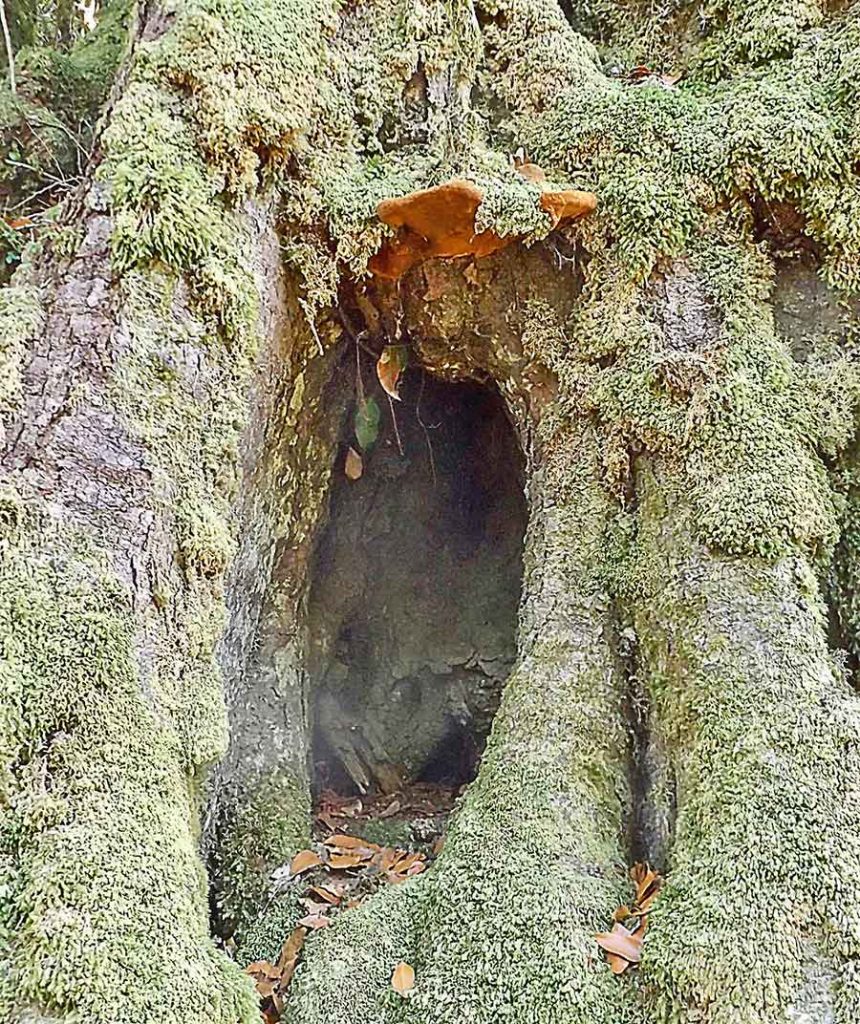

There is one public driving track in to the Lake Innes Nature from the Lake Cathie/Port Macquarie side, to Perch Hole Picnic area. And this beautiful serenity is what lies at the end of that track through a paperbark swamp.

Whether you look south or north, this large lake is impressive… and empty today save for one lone kayaker.

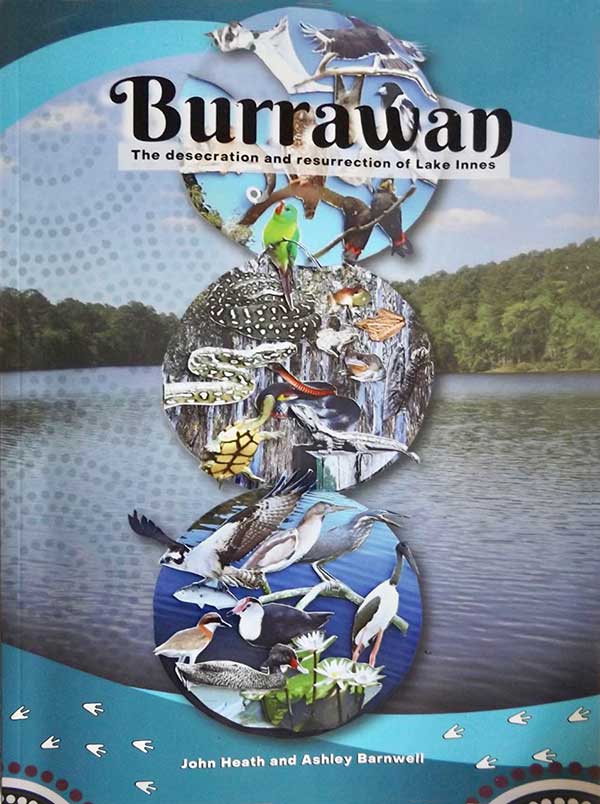

I was driven to go and see it for myself after being on the other side of Burrawan for the launch of a book about this lake.

In it, John Heath and Ashley Barnwell have compiled inforrnation and records about the story of this lake, offering both Birrpai and colonial ideas and histories.

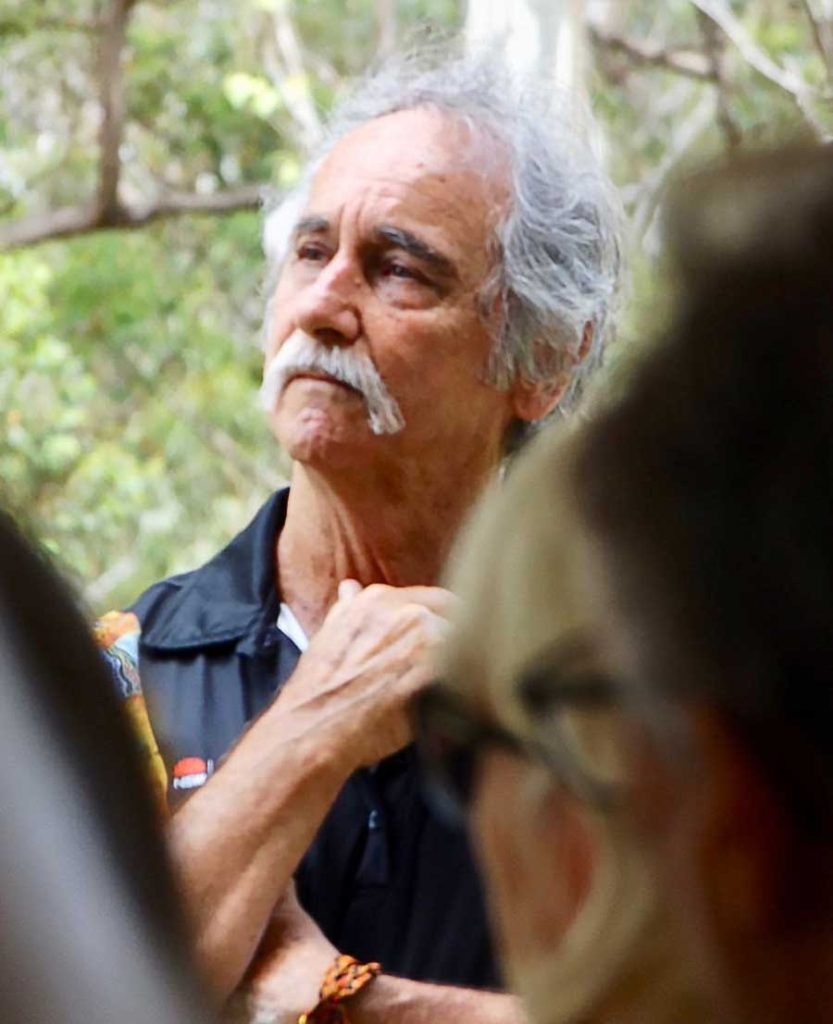

In front of the ruins of Major Innes’ brick home complex, once almost a small village, overlooking a grass sward that runs down to the lake, we were given some extraordinary insights.

The tall blue gums that would have totally blocked the view were long gone, and the lake was still visible behind John and Ashley as they listened to the speeches.

Major Innes had the trees cleared for his farming establishment, while his wife kindly introduced lovely garden plants, like lantana!

We were treated to a smoking ceremony and dances, mainly by John’s charming young relatives. The Birrpai were revered and applauded here today, but as the book shows, were not considered in Major Innes’s time.

But the shocker was that this lake was then freshwater, and is now salt… and all the plant and animal life that thrived on it had died.

Despite warnings, and never-realised intentions to build floodgates to stop the saltwater flowing back, a channel was dug by hand from Lake Cathie to Burrawan in the 1930s. The idea was to drain the lake and thus create 12,000 acres for farmland!

So, as the book summarises, the lake and all its wildlife and biodiversity was seen as merely submerged potential farmland.

Records from Albert Dick’s diary chart the demise of the rich life of the lake as the salinity increased, and they are truly shocking. I thank John and Ashley for this work, shocks and regrets notwithstanding; like massacres, we need to know the damage done by blind colonisation.

But you need to read the book! The Port Macquarie Historical Society has published this valuable resource and record and you can buy it from them or from John Heath.

Revive Lake Cathie is a group working hard to return Burrawan to fresh water — visit them here to find out more.