When this was built at the Mountain, I never imagined it would have to be moved. But it has, twice.

There was no way I was leaving it behind anywhere, but the last time was too much for it.

The beach pebble chimney survived its cracking, staying vertical and attached.

But I had to patch the ferro-cement roof– and pretty rough it is.

I am waiting for it to weather grey and gather lichen, to fit in.

But on the south side the roof has fitted in here beautifully, with the moss as thick and velvety green as ever.

Here the little cabin is placed right opposite my side steps, so I can sit and look at it, say hello as I pass…

This extract from The Woman on the Mountain, of the original construction and site, will show you why:

Dad’s place

It’s a pretty good place, with a view across the dam to the bush, terrific sunsets, and a couple of wattles just in front.Now how does that song go?… ‘It’s Ju-ly and the winter sun is shining, and the Cootamundra wattle is my friend… All at once my childhood never left me, ‘cause wattle blossom brings it back again.’

Yeah. And I got plenty of time for memories now.

My daughter often drops by for a chat, and my granddaughter brings my great-granddaughter to see me every few weeks. A right little card, she is, picks me fresh flowers every time she visits!

Much better than bein’ cooped up in one of them boxes, side-by-side with all the others, even if they do have landscapin’ and rose gardens. Give me this horse-cropped pasture any day.

We’d decided to build a cabin on my block for Dad. No reason why we three women couldn’t do it, if I kept the plan and method simple. My sisters had no building experience, but Dad wouldn’t care about rough edges and wonky lines.

As he’d been a carpenter by trade, I thought it best not to use timber; might make the mistakes too obvious, be an irritant, even for an easy-going bloke like Dad. Considering bushfires, and what was handy, a stone cabin seemed best.

I’d chosen a spot by the wattles, near some big rocks that would make perfect beer-o’clock sitting spots. My sisters arrived, and approved the site. We set to work. Citybased Sister One looked so funny in my spare gum boots and old felt hat that I wished Dad was here to see. She was to pass materials to me, while Sister Three was assigned to mixing cement.

We levelled the site, and boxed in for the slab. Our arms were aching by the time we’d mixed and trowelled and smoothed, but satisfyingly so. Sister Three went to make tea for smoko while Sister One and I watered and covered the setting concrete.

Next day we started the walls, leaving enough of the slab exposed for an all-round verandah. He’d want that to enjoy the view. It was a small cabin, but we fitted in a window on the eastern wall, for morning sun, and another on the northern wall, beside the door.

Dad loved an open fire, but Mum had put her foot down and insisted it be replaced by a less messy closed-in one, of a nasty shiny brown with a mean little mica window behind which the fire struggled for identity. It did warm the room, but not our hearts; it wasn’t even worth looking at, couldn’t conjure up a single flickering image or inspire a dreamy thought train…

So we made a big chimney on the west, where we could imagine him in front of a fine blaze, cooking his snags on it if he wanted. And making forbidden messes! Narrowing to a freestanding column, that chimney was a challenge, but ended up only slightly askew.

On the last evening of my sisters’ visit we drank to Dad as we admired our work, joking about what he’d think of it. He’d surely laugh at us girls as builders, especially Sister One who never went anywhere without makeup, and for whom a broken nail was a disaster. But for him she’d worked au natural and got dirty without complaint.

They had to return home, leaving the roof to me. Cutting tin was too hard, so I was using ferro-cement over chickenwire and hessian. Dad would shake his head at this unconventional method, but it would make a good watertight roof.

Now came the hard part. All the roofing materials ready, I went to get Dad. He had to move in now, because neither the door nor the windows of this cabin would open; my roof would close it forever.

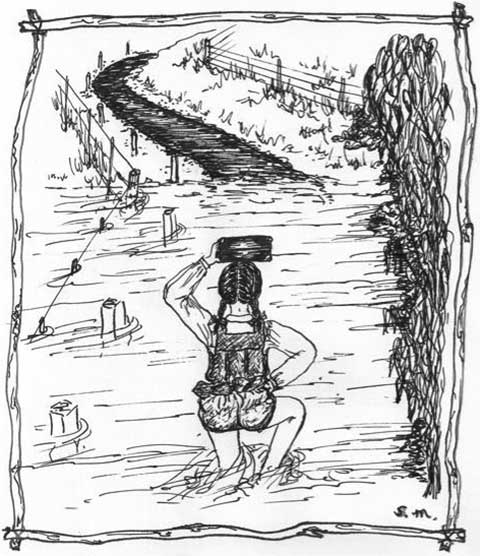

As I carried the grey plastic sealed box I could hear small shifting gritty sounds that made me tremble; these were more than ashes.

He fitted snugly in his cabin.I draped the hessian over the wire. He’s gone.

I hate doing this.

‘Sorry!’ I sobbed, as I worked the cement in.

Interment is… so… final.

It’s done.

Relief films over the hole in my heart.

Rest in peace, Dad.

I’ll be down for a beer tomorrow at 5.00. OK?

You can buy The Woman on the Mountain and my other books here.