The leaves have fallen from many of my garden trees and vines, so the seed pods are spectacularly visible. This White Cedar tree is a rare deciduous native, Melia Azedarach, often called Persian Lilac for its flowers, but also Bead Tree, for the now-obvious reason. They are indigenous to my region, amongst many others.

I have just pruned back the vines on my verandah, to reduce the build up of woody old growth (for bushfires), to promote new growth in spring, and to let in maximum winter sunlight. Before I did, I captured some of the masses of seed pods.

These are from the Chilean ‘jasmine’ (which it isn’t), Mandevilla laxa, whose scented white trumpet flowers produce hundreds of paired long skinny seed pods, now ‘popped’ apart and bursting with tiny feather-winged seed darts. They obligingly self-propagate.

These papery extra-terrestrials clawing skywards are from my very tall white lilliums.

The fat velvety brown pendulums of the White Wisteria do the opposite, hanging heavy, pointing to the soil where they want to land and grow. But these I will collect and attempt to aid the process in my glasshouse. The flowers are so ethereal I want more.

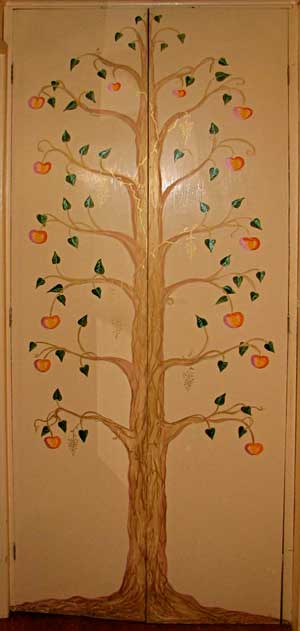

As the cold windy weather kept me indoors more, and with an unresolved writing project requiring distraction from mounting anxiety about it, I dug out the craft paints bought long ago — for a rainy day project. They’d been on a sale table somewhere; some were metallic, and colours were limited.

As the cold windy weather kept me indoors more, and with an unresolved writing project requiring distraction from mounting anxiety about it, I dug out the craft paints bought long ago — for a rainy day project. They’d been on a sale table somewhere; some were metallic, and colours were limited.

It’s Autumn, and my yard is being coloured– by more than autumn leaves.

It’s Autumn, and my yard is being coloured– by more than autumn leaves. The first bunches of wattle blossom have burst out of their tightly fisted buds — small explosions of powdery gold, honey-scented. I grew lots of these from seeds that fell from a tree in my Aunty Mary’s front yard in Sydney; we didn’t know what sort it was, but perhaps it’s a Queensland Silver Wattle (Acacia podalyriifolia)?

The first bunches of wattle blossom have burst out of their tightly fisted buds — small explosions of powdery gold, honey-scented. I grew lots of these from seeds that fell from a tree in my Aunty Mary’s front yard in Sydney; we didn’t know what sort it was, but perhaps it’s a Queensland Silver Wattle (Acacia podalyriifolia)? The bird-sown gift of a Pittosporum undulatum tree, also indigenous, has fruited its mini cumquat bunches for the first time. How did I miss the flowers? The bird didn’t plant it in the position I’d have chosen, but this has soared to such a height so quickly that it clearly found the perfect spot for the tree — if not for me!

The bird-sown gift of a Pittosporum undulatum tree, also indigenous, has fruited its mini cumquat bunches for the first time. How did I miss the flowers? The bird didn’t plant it in the position I’d have chosen, but this has soared to such a height so quickly that it clearly found the perfect spot for the tree — if not for me!

They seemed to be the only ones on the tree; luckily I refrained from picking one long enough to realise they were not seeds. Like Indian clubs, these smooth creations were hanging from a criss-cross of spider webs. I could just see the spider’s legs protruding from its dry leaf shelter (circled).

They seemed to be the only ones on the tree; luckily I refrained from picking one long enough to realise they were not seeds. Like Indian clubs, these smooth creations were hanging from a criss-cross of spider webs. I could just see the spider’s legs protruding from its dry leaf shelter (circled). The significance of ultra-abstract art often eludes me; I might appreciate it as design and colour, but it doesn’t speak to me. I don’t warm to it, relate to it, as I can to the merely abstracted, stylised, simplified, where the origin is vaguely discernible. In the latter the artist’s treatment of it stimulates my imagination more than straight realism would.

The significance of ultra-abstract art often eludes me; I might appreciate it as design and colour, but it doesn’t speak to me. I don’t warm to it, relate to it, as I can to the merely abstracted, stylised, simplified, where the origin is vaguely discernible. In the latter the artist’s treatment of it stimulates my imagination more than straight realism would. The cabin might be full, but I live in the midst of a forest that can dazzle me with temporary exhibitions of works of art like this one. The paint was fresh and bright after a spell of rain; a week later the colours will dull and fade, or flake off.

The cabin might be full, but I live in the midst of a forest that can dazzle me with temporary exhibitions of works of art like this one. The paint was fresh and bright after a spell of rain; a week later the colours will dull and fade, or flake off.