The walk below the cliff face at Woko National Park is all about green. Rock-edged paths wound up and down through the greenish light, as if in a carefully designed garden.

Not just green leaves, but mossed and lichened trunks and roots and vines, some of which curl like serpents around rocks and trees.

Thus securedly earthbound on the steep scree slope, they head skywards to the light. Sometimes the vines had overwhelmed the host with its weight and pulled it down, laden with staghorns or birds nest ferns.

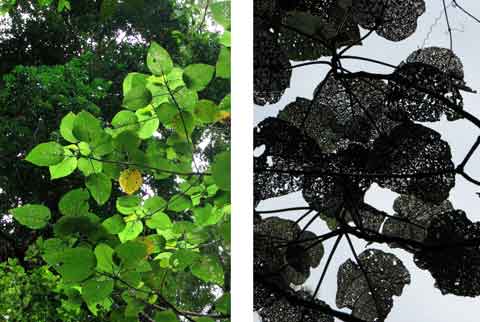

Some greens were to be avoided, like those of the Giant Stinging Tree, beautiful in the backlit canopy, whether alive, or dead and eaten into lacework.

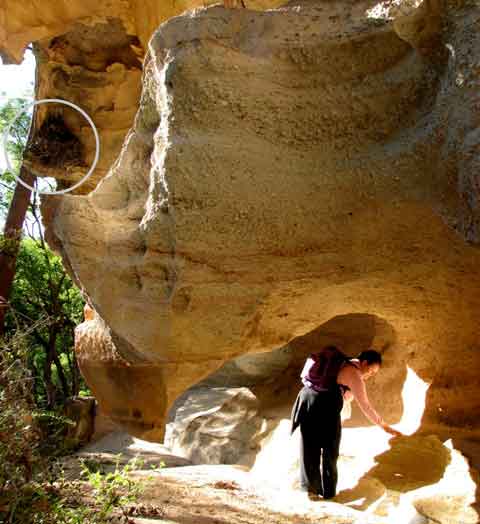

Looking up, the forest crept along the base of the cliff, where green struggled in crevices and clawholds to clothe the rock.

Looking out, where the rainforest had been breached by fallen trees, the view past the densely colonising vines was still all green, but of lighter, brighter shades as pastoral lands were revealed in the distance.

This tiny nest was made of living green lichen; small fantails had been seen nearby. This nest was empty, but others found one with a blue speckled egg inside.

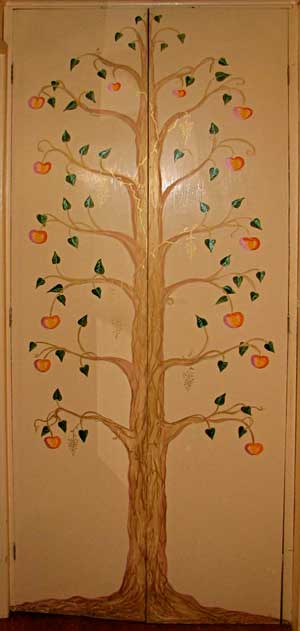

As the cold windy weather kept me indoors more, and with an unresolved writing project requiring distraction from mounting anxiety about it, I dug out the craft paints bought long ago — for a rainy day project. They’d been on a sale table somewhere; some were metallic, and colours were limited.

As the cold windy weather kept me indoors more, and with an unresolved writing project requiring distraction from mounting anxiety about it, I dug out the craft paints bought long ago — for a rainy day project. They’d been on a sale table somewhere; some were metallic, and colours were limited.